Published in: Uncategorised

Dantotsu in Software Engineering

During autumn 2022, I had the chance to attend the great FlowCon conference hosted in Paris, France, whose core topic targets stream delivery in software engineering. Lean, Agility and Continuous delivery are thus highly represented in the conference. One of the talks caught my attention, and I was far from disappointed when I saw it; The talk was realized by Woody Rousseau and Flavian Hautbois (The replay is in French here, and there’s a talk in English on the same topic made at the Craft Conference 2022). I can translate its title to “Radical Quality – from Toyota to IT.” In this post, I share some insights from this talk, especially the Dantotsu method, which was new to me.  Dantotsu means “Better than the best.” This radical approach challenges what companies usually settle to tackle quality issues. What are these ideas?

Dantotsu means “Better than the best.” This radical approach challenges what companies usually settle to tackle quality issues. What are these ideas?  Slide extracted from the conference. Here, we can see the deep level of details where they go to document what’s been wrong, and indicate that the countermeasure was to consolidate the tests. (Disclaimer: not surprisingly, consolidating the tests is a common countermeasure). NB: the two quoted companies in the conference used wiki-like systems to document these defects. Also, in their companies, they’ve set regular meetings dedicated to bugs. In these sessions, someone can present to the other participants a bug report and goes deep into the root cause and how to prevent it again. Similar to what happened in the Toyota factories, someone is showing the right gestures to avoid a problem happening again. If the sessions can be opened to anyone, it can also gather the Tech leaders, who will ensure the message is broadcasted to their respective teams. What were their conclusions after the implementation of this methodology? I won’t mention all the details, but here are some interesting insights: Pros:

Slide extracted from the conference. Here, we can see the deep level of details where they go to document what’s been wrong, and indicate that the countermeasure was to consolidate the tests. (Disclaimer: not surprisingly, consolidating the tests is a common countermeasure). NB: the two quoted companies in the conference used wiki-like systems to document these defects. Also, in their companies, they’ve set regular meetings dedicated to bugs. In these sessions, someone can present to the other participants a bug report and goes deep into the root cause and how to prevent it again. Similar to what happened in the Toyota factories, someone is showing the right gestures to avoid a problem happening again. If the sessions can be opened to anyone, it can also gather the Tech leaders, who will ensure the message is broadcasted to their respective teams. What were their conclusions after the implementation of this methodology? I won’t mention all the details, but here are some interesting insights: Pros:

Once the best practice has been validated, it can be shared with others teams in the organization, or within a community of practice. The knowledge is spread beyond teams.

Once the best practice has been validated, it can be shared with others teams in the organization, or within a community of practice. The knowledge is spread beyond teams.

What happened here is that we caught a bug and fixed it, and in addition, we capitalized on our work and generated a new best coding practice from it. We tried to follow the Dantotsu philosophy! If you have never heard about it before, I hope this short introduction helped you to get a better overview of Dantotsu. I’d be happy to have your feedback. Have you implemented the Dantotsu in your context? Please share!

What happened here is that we caught a bug and fixed it, and in addition, we capitalized on our work and generated a new best coding practice from it. We tried to follow the Dantotsu philosophy! If you have never heard about it before, I hope this short introduction helped you to get a better overview of Dantotsu. I’d be happy to have your feedback. Have you implemented the Dantotsu in your context? Please share!

Introducing Dantotsu and Radical Quality at Toyota

The talk relates the story of Sadao Nomura, who worked at Toyota between 2006 and 2015 to solve a pain point on quality issues. Before he joined Toyota, the company had a non-satisfying number of internal defects in its factory chains. Because of these bugs, it was common that the requirements to ship cars outside the factory weren’t met. Toyota really wanted to work on that to make sure the expected levels of quality were satisfied more frequently. And so Sadao Nomura came in. Sadao Nomura aimed to generate a 50% reduction in the number of defects on the factory chains for three years (meaning an overall ~88% of the global reduction for the full period). He told the full story in his book The Toyota Way of Dantotsu Radical Quality Improvement. Dantotsu means “Better than the best.” This radical approach challenges what companies usually settle to tackle quality issues. What are these ideas?

Dantotsu means “Better than the best.” This radical approach challenges what companies usually settle to tackle quality issues. What are these ideas? Dantotsu eradicates defects and ensure they won’t happen again

Why use the radical term when referring to Dantotsu? Because the philosophy isn’t about quickly fixing a defect, it’s also about deeply understanding why this defect happened, what’s been done to resolve it, and how to avoid this occurring again in the future. These are the core principles of Dantotsu. In the book, Nomura explains different aspects of the approach, particularly the importance of visual management and the training programs (Dojos), where workers can practice the right gestures to avoid defects. He also provides an interesting classification of the defects. In Tech, we often use the priority (Low/Medium/High…). He suggests using the four following types of bugs:- Type A: The defect is caught within the team and has no impact outside ;

- Type B: The defect goes to another team within the company ;

- Type C: The defect is undergone by a third party or subcontractor ;

- Type D: The defect is undergone by the customer/final user (the worst situation, of course).

- the team leader in charge of the area first makes sure that no other pieces have the same issue;

- the root cause of the issue is identified and fixed;

- counter-measures are taken to avoid the defect from happening again;

- a report is shared with the whole team to explain the 3 previous points;

- It doesn’t stop here. The team leader also reports to other team leaders of areas where a similar defect can occur, and they’re trained to fix the issue as well.

Dantotsu in Software Engineering?

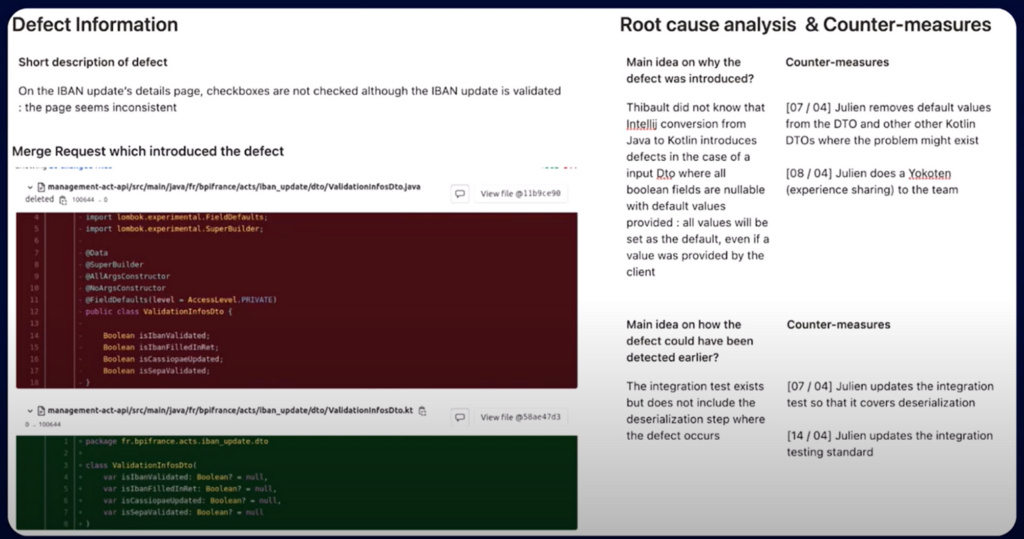

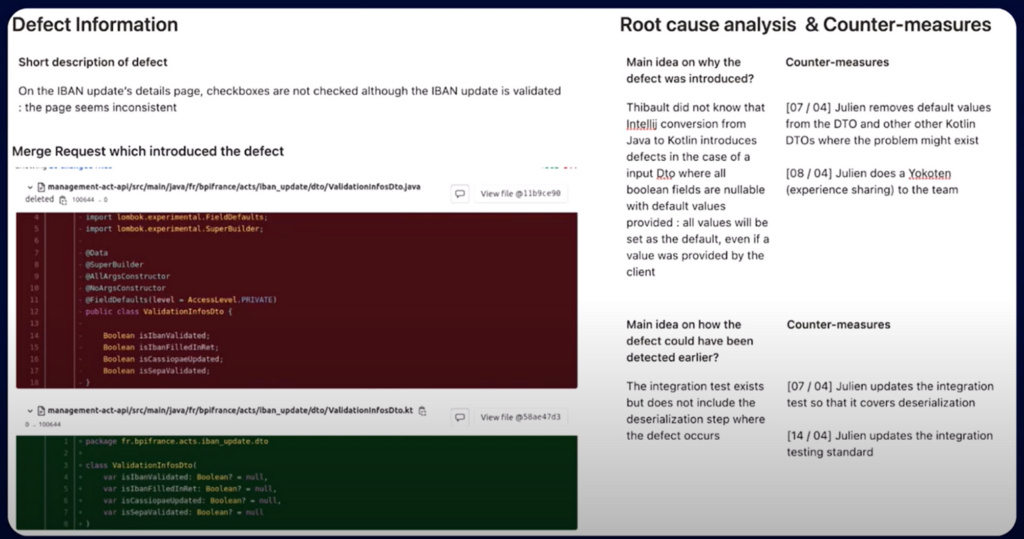

The second part of the talk was about how the Dantotsu method was implemented in two tech companies. They recall that, in software engineering, there’s still work to do to convince people that doing things right costs less than non-quality (surprising, right?). If you’re skeptical about this statement, we recommend you to read The Economics of Software Quality which precisely demonstrates the cost of bad software quality. The Accelerate book closes the discussion on that question if it’s still needed. The two speakers in the talk explain that to reach the zero-defect (utopian) ambition, the key part is to train developers to produce source code with no defects. They also transpose the bug categorization into the software engineering world, so, for instance, Type A is a defect caught by developers locally or during the continuous integration step. In their respective company, they’ve both implemented a new process where defects are documented, especially the investigation and the countermeasure. Here’s a capture of one slide that encompasses all the information: Slide extracted from the conference. Here, we can see the deep level of details where they go to document what’s been wrong, and indicate that the countermeasure was to consolidate the tests. (Disclaimer: not surprisingly, consolidating the tests is a common countermeasure). NB: the two quoted companies in the conference used wiki-like systems to document these defects. Also, in their companies, they’ve set regular meetings dedicated to bugs. In these sessions, someone can present to the other participants a bug report and goes deep into the root cause and how to prevent it again. Similar to what happened in the Toyota factories, someone is showing the right gestures to avoid a problem happening again. If the sessions can be opened to anyone, it can also gather the Tech leaders, who will ensure the message is broadcasted to their respective teams. What were their conclusions after the implementation of this methodology? I won’t mention all the details, but here are some interesting insights: Pros:

Slide extracted from the conference. Here, we can see the deep level of details where they go to document what’s been wrong, and indicate that the countermeasure was to consolidate the tests. (Disclaimer: not surprisingly, consolidating the tests is a common countermeasure). NB: the two quoted companies in the conference used wiki-like systems to document these defects. Also, in their companies, they’ve set regular meetings dedicated to bugs. In these sessions, someone can present to the other participants a bug report and goes deep into the root cause and how to prevent it again. Similar to what happened in the Toyota factories, someone is showing the right gestures to avoid a problem happening again. If the sessions can be opened to anyone, it can also gather the Tech leaders, who will ensure the message is broadcasted to their respective teams. What were their conclusions after the implementation of this methodology? I won’t mention all the details, but here are some interesting insights: Pros: - A strengthened culture of software quality and more open discussions around bugs;

- One of the speaker’s team achieved an 81% decrease in defects in production in 3 quarters. The trend is less visible at the company level, even though it is positive, but it’s a longer-term goal to show results at this level;

- For the other speaker, they had a 50% reduction of new bugs in production in 3 quarters, and also, they got twice more bugs resolved in less than 24 hours.

- Hard to address the stock of bugs, especially if they were introduced several months ago. Speakers talk about doing Archaeology sometimes;

- A deep analysis of a bug requires time (~2 hours) for someone trained, but Tech Lead has others duties in their work. So there’s a balance to find;

- Sometimes discussions go beyond technical aspects, to address collaboration issues related to communication or pressures on delivery (that still need to be solved as well).

Dantotsu: From Defect to Best Coding Practices

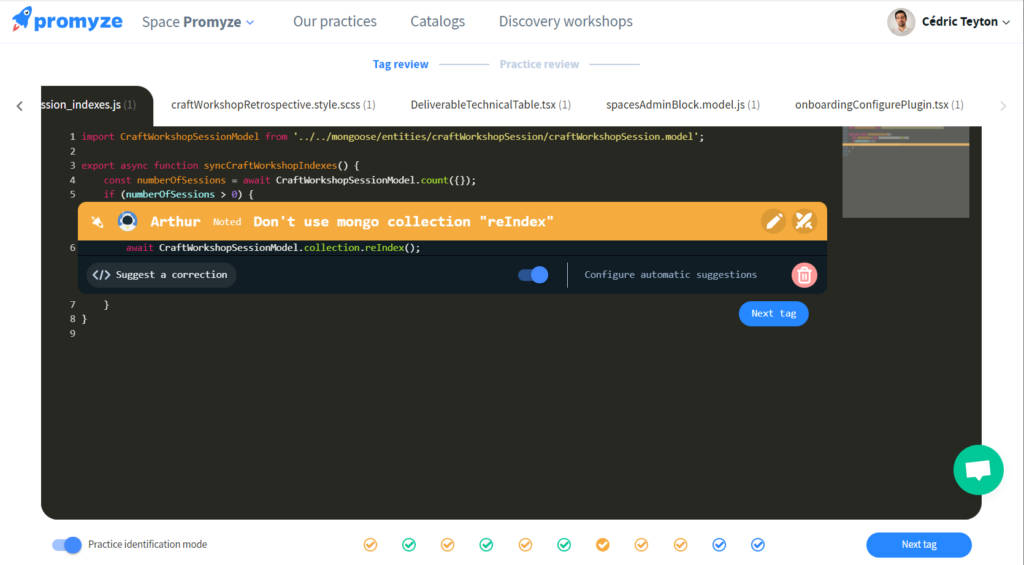

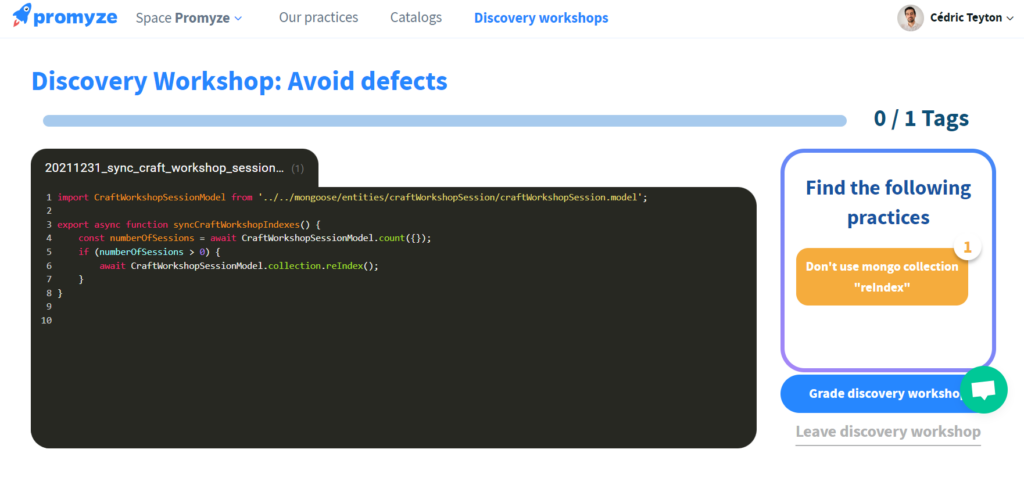

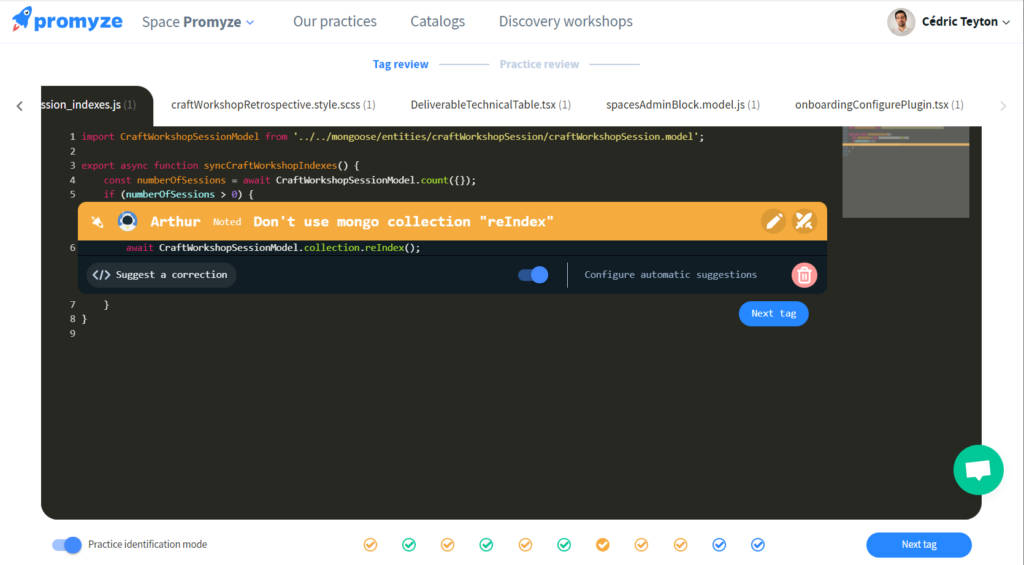

We saw that when a bug is found in the source code and fixed, this should be turned into shared knowledge for the team (so that it won’t happen again, remember?). That’s what’s shown in the screenshot above. An easy way to perform this operation is to use the Packmind platform, which aims to ease best practices sharing in engineering teams with deep integration in developers’ tools (IDE & Code Reviews). Developers are keen on sharing best practices in many situations, such as performance improvement, security fixes, better readability, or bug fix. Let’s see an example of how to proceed with a concrete example of a defect fixed in late 2022 internally. In our staging environment, before a final release, we spotted an error when our application started and performed patches on the MongoDB database. In our code, a method from the Mongoose framework was called to regenerate the indexes of a collection. We observed runtime issues and found this method should rather not be called in our context (this last point is an important precision; I’m not saying you should never call this method, but in short, it wasn’t compatible with our system). Let’s see how we propose to adapt the Dantotsu process to Packmind.1. Identify the defect & define best coding practices to fix it

The defect has been spotted in the code, and we removed the call to reIndex(). Before that, we created a best practice from VSCode using the Packmind extension: Selection of code → Right Click → Promyze → Identify a new best practice. Just put a name, and this is sent to the Promyze application.

2. Report your best coding practices to your team & beyond

Then, with Packmind, our team (a project team, feature team, or even a community of practice) runs regular workshops to review best practices proposals. Each contributor explains the intent behind the suggested practice. In our case, Arthur explained to the whole team the issue met with the reIndex function call, and everyone could indicate if this was clear to them. Once the best practice has been validated, it can be shared with others teams in the organization, or within a community of practice. The knowledge is spread beyond teams.

Once the best practice has been validated, it can be shared with others teams in the organization, or within a community of practice. The knowledge is spread beyond teams. 3. Implement countermeasures

Once a best practice has been validated, you can set regular expressions that match the pattern you want to avoid to push notifications in developers’ IDE and Code reviews (a linter-like behavior). This will be possible if your pattern can be matched by the syntax of the code. It will reduce the risk that this method will be used in the future. This is what it looks like when configuring a regex in Packmind, and then getting suggestions in VSCode:

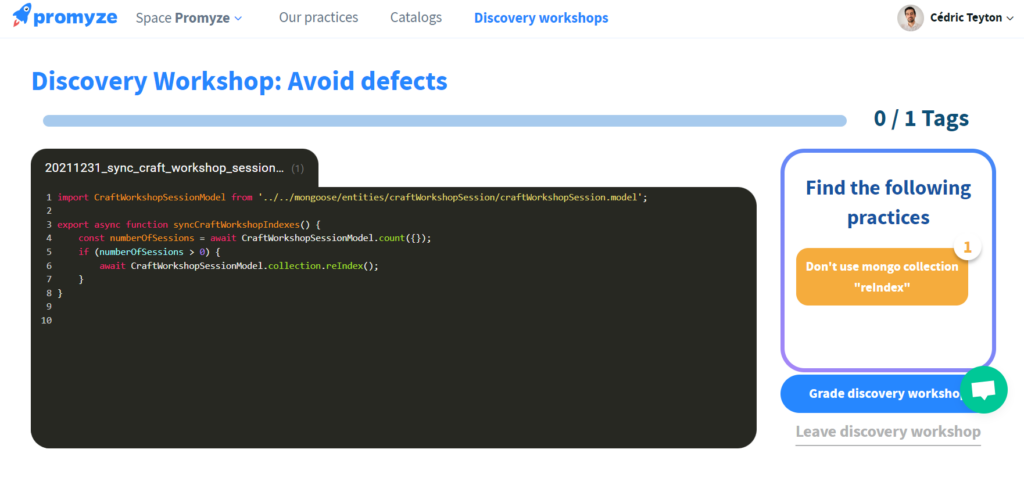

4. Teach your best coding practices to your team

When new developers join your organization, they need to get familiar with your best coding practices, and also the patterns to avoid defects. In Promyze, there is a feature called onboarding workshop for new hires, where they can train on your knowledge base. As each best practice has associated code files, each recruit will be invited to locate the area where the best practice has been followed (or, inversely, not applied). In the example below, they’ll need to highlight line number 6: What happened here is that we caught a bug and fixed it, and in addition, we capitalized on our work and generated a new best coding practice from it. We tried to follow the Dantotsu philosophy! If you have never heard about it before, I hope this short introduction helped you to get a better overview of Dantotsu. I’d be happy to have your feedback. Have you implemented the Dantotsu in your context? Please share!

What happened here is that we caught a bug and fixed it, and in addition, we capitalized on our work and generated a new best coding practice from it. We tried to follow the Dantotsu philosophy! If you have never heard about it before, I hope this short introduction helped you to get a better overview of Dantotsu. I’d be happy to have your feedback. Have you implemented the Dantotsu in your context? Please share!